FIELD NOTES | REFLECTIONS

Baldwin’s field notes illustrate the moments that mobilized her activism. These excerpts from Baldwin’s field notes distill the evidence from many hours of recordings to help NGOs fighting for environmental and human rights, such as International Rivers and Survival International.

The power of Kara Women Speak is not only about select excerpts from the women’s stories. These field notes become more powerful when combined with multimedia archives of the entire project — such as following one woman’s challenges in a documentary film, looking eye-to-eye at a life-sized portrait while hearing songs of lullabies during an exhibition, hearing the sounds of the natural landscape in audio recordings, and sitting with images and everyday life stories when reading publications.

The body of work has the power to forge connections with the landscape and people of the region. Kara Women Speak connects a global audience to the real people, Indigenous women facing the impact of the extraction of natural resources.

Ethiopia’s Changing Omo River Valley, 2005–2014

By Jane Baldwin

Korcho Village, Omo River Valley, Ethiopia © Jane Baldwin

Click images to enlarge

SEPTEMBER 2014

My first trip to the Omo River Valley was in 2005, and I have returned annually to document the lives of women in the remote Omo Valley and Lake Turkana. Kara Women Speak is a ten-year multimedia project about the Omo River cultures from the women’s point of view, and the human rights and environmental issues that now threaten their way of life. This body of work tells their stories through portrait photography, recorded interviews, and field recordings of ambient sounds, social media, film and video.

Over the course of the decade, I became intimately connected with the women of the Kara, Hamar, Kwegu, Nyangatom, Dassanech, Mursi, and Turkana communities who have lived for centuries unaffected by colonialism or modernity. Grave human rights abuses and environmental destruction now threaten their way of life. The Gibe III dam being built on the upper Omo River will forever change the flood cycles that deposit essential nutrient-rich silt along the riverbank that makes their land productive. The loss of annual deposits of silt-laden floodwaters and grazing land will create food shortages and increase Tribal and inter-tribal conflict.

These notes from the field reflect my personal experiences and observations of a decade working with women and their communities in Ethiopia’s Omo River Valley and Kenya’s Lake Turkana.

2014 | NOTES FROM THE FIELD

Indigenous Omo River cultures have been living self-sustainably for hundreds of years. They grow their own food, make their own clothes from the leathers of their goats, and forage wild fruits, seeds, and edible plants from the forest. They harvest honey from their beehives and gather medicinal plants. The Omo River provides fish and abundant water for their cattle, goats and agriculture. And they trade with other Tribes for the few necessities they do not produce themselves. This self-sustaining lifestyle is rapidly changing. I returned to Ethiopia’s Omo River Valley on September 19, 2014. Since 2012, massive tracts of Kara ancestral forests and bush-land have been bulldozed and laid bare (See before and after photos above). Land grabs [1] are well under way. The Ethiopian Government has seized and leased thousands of hectares of land to the Omo Valley Farm Cooperative PLC, operated by a Turkish agribusiness company to plant cotton—all without compensation or consultation with the Kara or other indigenous communities of the Omo River Valley. This is only one of many land leases going on in the Lower Omo.

The Kara have been marginalized by these changes. Thousands of hectares of Kara bush-land and forests, which supported their self-sufficient way of life, have been decimated. The valley is now a wasteland of ripped trees pushed into huge piles of brush and dead wood throughout the valley. All Kara villages are now squeezed between a huge cotton farm and the Omo River. Their land is no longer available to graze their cattle, and they were forced to move about 4,000 head of cattle to the Mago National Park area, 30–40 km north of their villages. The people now have only a limited number of goats for milk and meat. Since most of their forests and lands have been decimated, the abundance of seasonal wild food to forage has become inadequate. The loss of wild fruits, nuts and honey and natural medicines is reaching crisis levels for many.

The harmony and balance of the ecosystem I first experienced from 2005–2012 has disappeared. I could no longer hear the rich sounds of the natural world. Gone are the vocalizations of the Fish Eagle and Egyptian Ibis, Vervet monkeys, baboons, bees, and the night pulse and sounds of insects and frogs.

One clear sign that this is a dramatically changed landscape is the unnatural quiet in what was once an area of rich soundscapes. All wild and natural landscapes around the world have a unique soundscape and each has its own distinctive signature expression. Every soundscape has three different layers of sounds that include insects, birds, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians, and each vocalize at its own specific sonic bandwidth. The huge changes to the Omo River eco-systems reveals how rapidly the balance and health of the Omo River Valley and Omo River have declined.

The Kara women work hard to hold their communities together, and have always done the heavy work. They care for their children, carry water from the river, thresh the sorghum, gather wood for their fires, and still seem energetic, optimistic and proud.

[1]

Defining Land-grabs:

Land-grabs are a global phenomenon led by local, national and transnational elites, investors, and governments with the aim of controlling the world’s most precious resources [water and land]. Land-grabs displace and dislocate communities, destroy local economies and the social-cultural fabric, and jeopardize the identities of communities, be they farmers, pastoralists, or Indigenous peoples. Those who stand up for their rights are [sometimes] beaten, jailed and killed. — Via Campesina, International Peasant Movement 2012

Land-grabs are deals that lack free, prior and informed consent by land-users, do not include socio-environmental impact assessments, and are carried out corruptly and without proper democratic participation. — International Land Coalition

On my most recent trip, the women were noticeably tired and thinner. Babies seemed to have more infections than in previous years. The women showed less pride than in prior years. The men are losing their role within their culture and seem powerless to resist the takeover of their ancestral land. I’ve been told that Government people and “highlanders” drive down from the north to sell them Araki (a type of moonshine). Alcoholism is on the rise.

The Ethiopian Government recently attempted to move a Hamar community off their land to make room for other transnational agri-business farms to plant cash crops of cotton, palm and sugarcane – all for export. All Omo River communities are at risk of such projects and face forced evictions and relocations.

Villagization [2] has begun. The government built a small Hamar resettlement village, but the Hamar have refused to move into it. It now sits empty.

The events unfolding in the Lower Omo River Valley are yet another example of what’s happening to disenfranchised people around the world. Most Omo River cultures are agro-pastoralists and practice flood-recession agriculture. All depend on the river’s natural flood cycle to replenish their land for farming and grazing of livestock. These Indigenous communities are now faced with forced removal from their ancestral land and water. They have no land or water rights. They have told me that no one has come to talk with them about these changes, and that they have no voice in any discussions about their future.

[2]

2005 – 2010 | EARLY YEARS & FIRST IMPRESSIONS

In 2004, I joined four other photographers and conservationists on a low-level flying expedition following the great rivers and waterways that define life in Africa. We flew over 5900 miles in a six seat Cessna 210 airplane, traveling from the Blue Nile’s source in Ethiopia to Cape Town, South Africa. It was on this trip I first heard about Ethiopia’s Omo River Valley. In 2005, I made my first trip to the Omo River Valley—considered to be the most culturally diverse region in Africa, and returned annually. On this first trip, I met my guide in Murelle and we drove through the bush to camp, which was located on a bluff overlooking the Omo River. Our camp site and sleeping tents were shaded by Cape Mahogany trees.

Time took on another dimension. There was a rhythm to the land that became palpable. The smells, scents and ambient sounds of the natural world seemed to define ‘time.’ At dusk, as the sun faded and as the land cooled, the scent of the river and air took on the smell of tannins, much like musky tea. Western time was no longer relevant. I took off my watch.

Villagization: “Villagization is a vast resettlement scheme to move local ethnic people into designated villages by government or military authorities; often compulsory.” — Collins English Dictionary

Near the Murelle airstrip, Omo River Valley, Ethiopia, 2010

© photographs by Jane Baldwin

The ambient sounds of the day and night marked the passage of time. After dusk the vocalizations of insects and frogs softly filled the air accompanied by the occasional grunt of a mother Nile crocodile calling her young. Early in the morning Colobus monkeys called to each other back and forth across the Omo. The Fish Eagle and Egyptian Ibis screeched as they began to feed. At sunrise and sunset African honeybees could be heard coming and going from their hives.

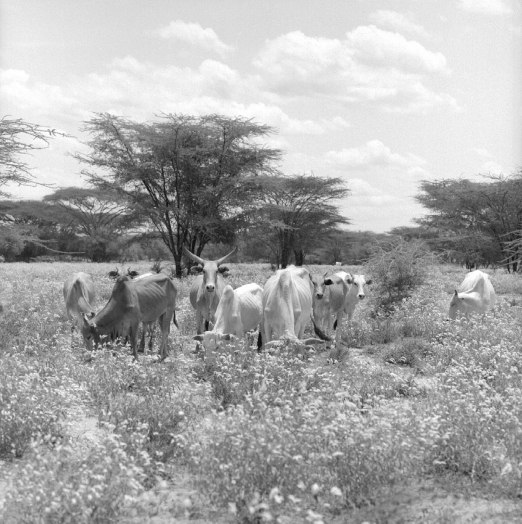

In March 2010, when we landed at the Murelle bush airstrip, the land was in full flower and carpeted in white blossoms to the horizon. I’d never been to the Omo this time of year. The air smelled of honey. The cattle, goats and sheep grazed belly-high in the blooms of flowers and fresh grass.

The next morning, as I sat next to my tent over looking the Omo, I felt an overwhelming reverence for the land and people. Thousands of white butterflies were everywhere; the air smelled sweet and honeybees could be heard leaving their hive. I was immersed in the surreal beauty of the natural world that seemed to transcend reality—a place one only reads about in literature, and imagines. This was an ecosystem in perfect harmony and balance.

2009 – 2014 | CONVERSATIONS WITH WOMEN

Omo River cultures are patriarchal. In these patriarchal societies women rarely have a voice and their stories often go untold. Women are the nurturers of their communities and families. They are valued for the number of children they bear and for their hard work, but they are seldom engaged for their thoughts and ideas.

Kara women were often in camp passing through to collect water from the river. On my first trip, I noticed that when the Kara women came into camp they’d linger in the background. They seemed curious to connect. One day I approached them and we began to sit together, finding ways other than a common language to communicate. I wanted to learn more and enlisted my guide and a young Hamar woman to translate for me. In 2009, I began to interview women and record their cultural stories and their role within it. They were eager to talk about their lives and their concerns for the future of their people.

Women are the heartbeat of all Omo cultures, but rarely have an opportunity to express their opinions. They are keepers of their oral traditions that pass down the narratives of their ancestry and families. Through this oral tradition of storytelling and song, they keep their cultural and family histories alive.

REFLECTIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Throughout my decade of travels in the region, I traveled by boat up and down the Omo River to visit with women of Indigenous communities. The Kwegu and Nyangatom are isolated and live on the Sudan side of the river. The Kara and Mursi were accessible on the east side of the river. The Dassanech live in the delta, a remote area of islands and marshes along the Kenyan border. The Turkana live around the shores of Kenya’s Lake Turkana, and the Omo River provides about 90% of the lake’s water. Without a boat, most of these villages would not have been accessible. During my ten years of travel along the Omo I never saw another boat except kouros, made from trees that the local men use to navigate the river. The Hamar were within a short day’s drive and on occasion, I’d sometimes camp overnight at a Hamar compound.

Omo River cultures possess a highly sophisticated system of rain-fed farming which allows their crops to thrive often under difficult conditions. Their village seed banks contain different varieties of sorghum and peas. They have an intimate understanding of Omo River flood cycles. Hundreds of thousands of people live in this watershed. They are at risk of eviction from their land; Tribal and inter-tribal conflict will almost certainly worsen as diminishing resources disappear. Without access to their land, their food security and livelihoods are in peril. Government people and contract farmers could also get pulled into the conflict.

In September 2014, as I left the Omo River, it was clear to me that these cultures would soon be quashed by their government and outside influences. I don’t feel I can end this paper without reflecting on the global history of Indigenous peoples’. In the 21st century, effort by governments and huge multinational corporations to acquire land and water rights throughout Ethiopia and Africa, seems to be repeating itself. Conditions are being created that will bring about the physical and cultural decline of all Indigenous Omo River Valley communities. I believe it’s only a matter of time before sickness and malnutrition permanently take root. The influx of massive farms is slowly wedging the Kara and other Indigenous people up against the Omo River without any place for them to go. The reduced access to their ancestral land, their ability to be self-sustaining and provide for themselves is now endangered. If nothing changes, the people of the Omo will be scattered and their cultures will disappear.

To be successful, how can long-term land leases by the Ethiopian government (or any government) to foreign corporations be sustainable without the participation of the local Indigenous people? How does a government measure success? A Nyangatom elder recently said, “Don’t just think of today, but think of tomorrow, and the future’s future.” In the Omo Valley, it seems that tomorrow may be a much darker, more difficult place for the Indigenous peoples’. And the world will be a lesser place without these vibrant and resourceful cultures.

As an artist with a deep connection to the Omo People, I hope my insights and personal experiences of this region can help illuminate the serious consequences facing these self-sustaining, vulnerable, proud and dignified people. These testimonies and stories from women give voice to people on the verge of displacement from their ancestral land and loss of cultural identity and way of life.

National Geographic Magazine | March 10, 2010

Click image to enlarge